All The Things I Didn't Know Were OCD

If you follow me, there's a decent chance you have OCD too.

The first time I remember having an OCD intrusive thought was when I was about nine or ten. I was getting lunch from my school cafeteria, and once I had gotten my burger, fries and milk, I realized I needed to pick a straw for my milk. The straws were all in the same repository, all of them identical. It didn’t matter which straw I picked. But for some reason, I had the thought: if you pick the wrong straw, your parents and brother will die. No, don’t pick the straw you saw first, that’s the death straw. Pick another straw. Uhhh..never mind, kinda getting a bad feeling about that straw too.

I picked what I believed to be the “right” straw and what do you know—my parents and brother didn’t die.

The fact that I had this thought at all told me something else: I had the power to foresee horrible things. This meant that next time I had a similar thought, I would need to listen to it and act accordingly to prevent disaster. I knew logically that there was no physical mechanism by which the selection of the “wrong” plastic straw would kill my family. But who cared? It was just one straw, just a few seconds of rumination. Surely, it would be a harmless superstition to do what my “gut” instructed me to do. Wasn’t I supposed to trust my gut, after all?

I didn’t share this information with my parents because it didn’t feel important. Also, I had never heard of OCD before.

The first time I actually heard about OCD I was fourteen, and unbeknownst to me, I was suffering from it pretty severely. My OCD at this age revolved around the fear that I would never get married or have children, along with the fear of my family dying because of something that I did. Because both of these things were technically possible, they didn’t seem irrational. The things I did to “prevent” them from happening also felt normal. For example, I prayed every night, often repetitively (I was brought up in a mixed faith household and not raised with any religion; my entrance into faith might have been fueled at least in part by my OCD.) I would also write in my diary about things I was afraid of happening—perfectly normal behavior for a teenage girl. And then there was my tendency toward hypochondria (especially related to illnesses that would impact my fertility), but that didn’t seem so weird—I just went to the school nurse more than most kids did, and there was nothing wrong with taking care of your health.

Anyway, I first heard about OCD when I watched the movie Matchstick Men, where Nicholas Cage’s character is borderline housebound with OCD. Leaving the house, or opening a window, causes him to have terrifying delusions of visible germs and spores floating toward him. I remember mentioning the movie to my friends at school, and one of them said that he didn’t find the movie funny because his father had OCD. I laughed to myself and thought his father’s OCD was probably pretty funny too.

Generally, that was how OCD was portrayed most of the time. This was before social media, so I wasn’t hearing from other people with OCD about all the various insidious forms it could take (on the bright side, I also wasn’t seeing TikTok users refer to their “intrusive thoughts” as the urge to eat a carrot salad for breakfast). All I had was movies and TV shows, which conveniently always displayed the OCD sufferer as a germaphobe.

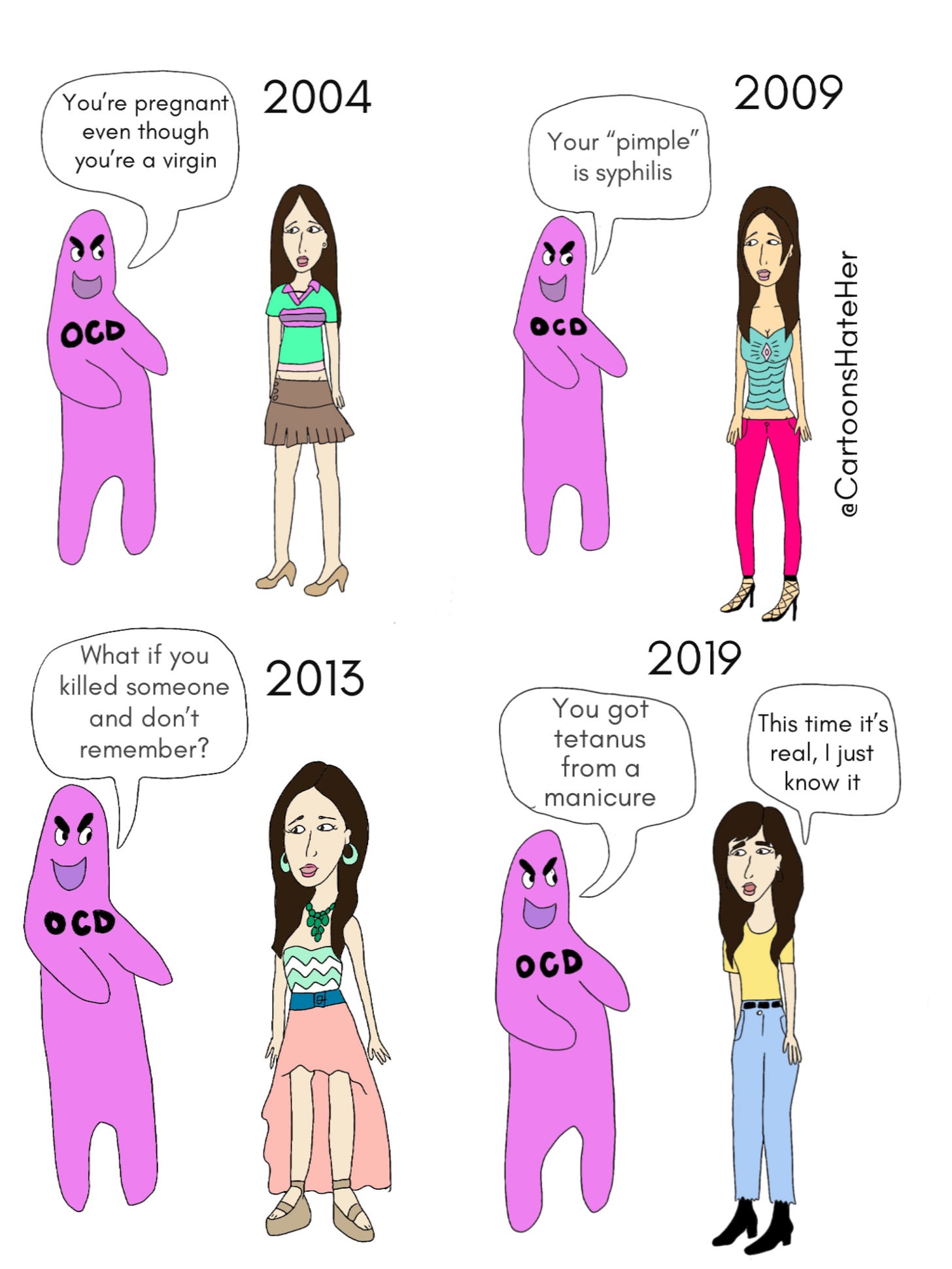

Ironically, I wasn’t diagnosed with OCD until I developed a germaphobia obsession myself. The following comic illustrates the journey of how each obsession was replaced with another:

My longstanding fear of never marrying or having children had turned into a fear of catching an STI, specifically an incurable STI that I feared would make it harder for me to find a husband someday. I had lost my virginity in high school, but decided to be celibate for a year after that, primarily because I was too afraid of the risks (if I had been a boy, I’m convinced being “voluntarily celibate” would have sounded like a convenient excuse for not pulling any pussy.)

Obligatory: I am now aware that having an STI, even a lifelong one, does not make someone unlovable or unworthy. But I was a teenager in the mid-2000s, and this is just what I felt at the time. I still believed that getting HIV, for example, would be a death sentence. And while the idea of me contracting HIV sounds pretty absurd, I was under the impression that I could catch it from microscopic blood drops on various surfaces, or from kissing someone. Google searches told me this wasn’t possible, but I kept wondering if maybe it was possible—unlikely, but possible, like a 0.0001% chance—and I would get unlucky. And OCD can often align itself with fears that are “problematic” or offensive in some way, which makes it harder for the sufferer to talk about it. For example, it’s not uncommon for people with OCD to worry that they’re secretly gay. It’s not because they hate gay people but rather because they’re worried about choosing the wrong partner, not really being attracted to them, living their life regretting their choices, and so on. And these are actually pretty “vanilla” obsessions in the grand scheme of OCD. It can get pretty weird. Either way, no matter what someone’s OCD obsession is, it’s not their fault nor is it representative of their true beliefs.

Anyway, my obsession with getting herpes from my own Venus Intuition razor, let alone other people, unsurprisingly made it really difficult to date. Even though I wanted boyfriends, and dating took up a huge chunk of my emotional energy, there was another upsetting layer to every relationship which was how I would avoid the level of physical contact that I worried would be dangerous. I also wanted to casually gauge the likelihood that any partner of mine might have an STI, by asking “random” questions like, “So, by the way, have you ever had a cold sore? Do you know if you got it from family kisses or from something else?” I didn’t want to date boys who were too experienced, partially because of my fear of STIs but also because I was afraid they would expect more from me than I was willing to do. But even dating less experienced boys brought its own struggles. When I was a senior in high school, my (not very experienced or popular) boyfriend told me he played a game with some of his friends that involved repeatedly spinning a coin against their knuckles, which caused bleeding (this is what teenage boys were doing before Skibidi Toilet.) I was terrified that he had contracted HIV or hepatitis C from any of the friends. I had the urge to track down the friends and interrogate them about any amateur tattoos they had gotten, who they had slept with, or whether they had ever had a blood transfusion.

The funny thing about my oblivion toward my own OCD was that I was in therapy all this time for general “anxiety issues” and none of my therapists had picked up on my fairly obvious affliction with OCD. As a teenage girl, I noticed that therapists defaulted to assuming I had low self esteem and blaming that for all my problems. Granted, I probably did have low self esteem, but I also had OCD. I was familiar with OCD by then, but I was under the impression that OCD needed a compulsion. I didn’t realize that the Googling, the research, and the asking for reassurance was my compulsion. I didn’t realize anything until I developed a very textbook compulsion: washing my hands nine times every time I used a public bathroom. At this point, my therapist confirmed what was so obvious in hindsight. I had OCD.

There are many things that make OCD difficult to treat, but the three main things are (in my unprofessional opinion):

The subtype doesn’t matter. For years, I would try to “solve” my obsessions in therapy by trying to figure out why I was so afraid of being alone, or why I was so scared of my mom dying, or why I thought I was going to get hepatitis C from touching a doorknob. Did I not believe I deserved happiness? Did I secretly not want children or marriage? Ultimately, none of it mattered—what mattered was my behavior, and the fact that I kept doing my compulsions. Often the obsession itself is random and irrelevant. But because I was in talk therapy, not behavioral therapy, I kept ruminating over the meanings of my compulsions. Funny enough: rumination is also a compulsion! It literally just made everything worse!

You need to do exposures. “Exposures” are basically exposing yourself to the thing your OCD makes you avoid, and then resisting the urge to do whatever compulsions usually make you feel better. For me, it wouldn’t have made sense to purposefully contract an STI, so I struggled with not knowing how to do an exposure. What I probably needed was an incidental exposure—wait until the next time I thought I was in danger of catching an STI, and then resist the urge to Google it. For example: use a public bathroom the way a normal person would, no weird rituals other than washing my hands once.

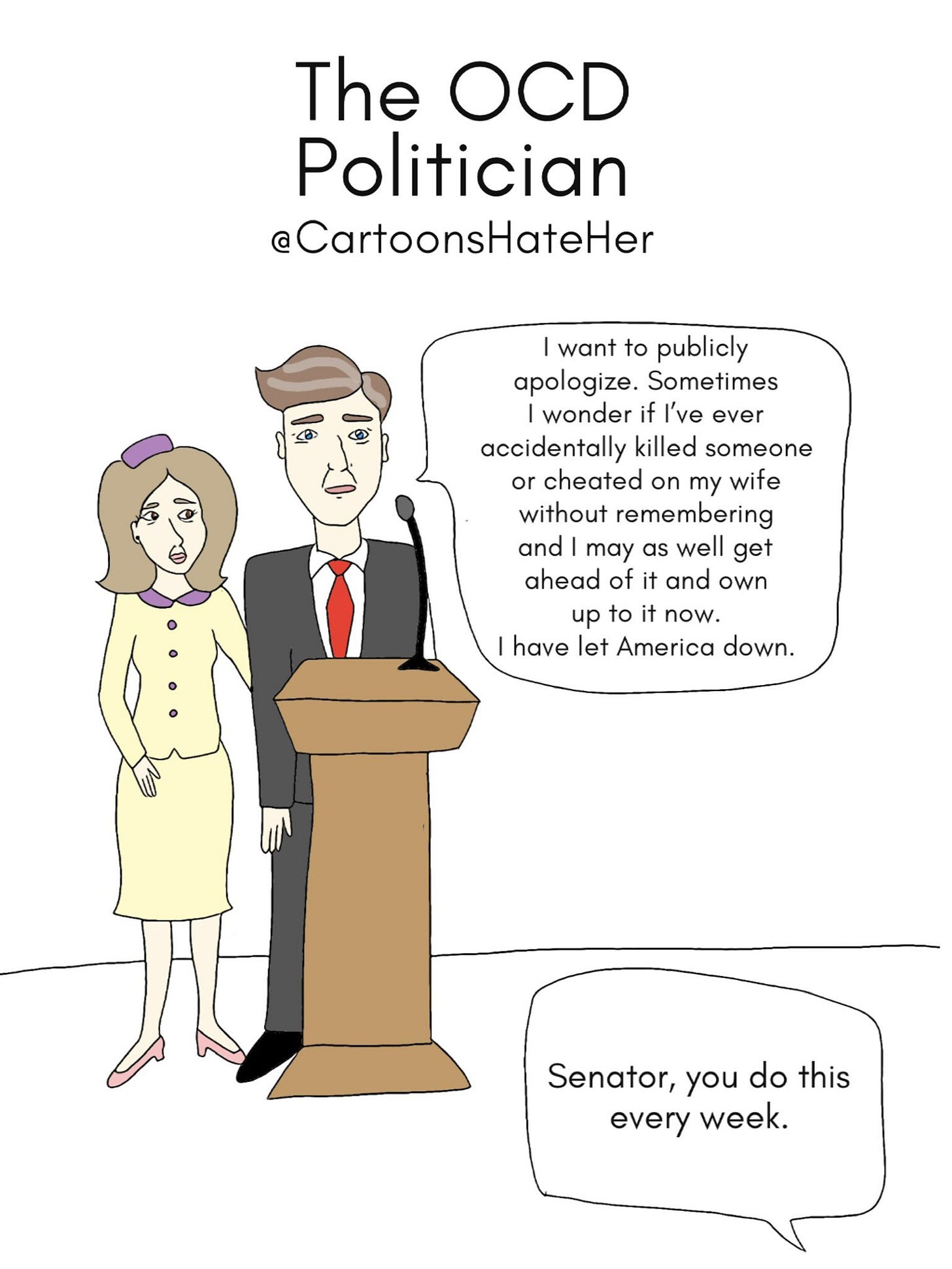

The subtype will change. I finally got diagnosed with OCD when I developed a very textbook subtype (germaphobia/hand washing.) But that obsession didn’t last for long. I met my husband around this time, and my OCD began revolving around the fear of him getting into a car accident. My compulsion was texting him asking him if he arrived somewhere safely. If I drank even a little bit of alcohol (we were in college; there was plenty of drinking) I would worry that I had blacked out and said horrible things about him, or cheated on him. With this obsession, my compulsion was texting all the people I had seen the night before and asking them what I had done, despite not having been drunk enough to black out. The tricky thing about the shapeshifting obsessions and subtypes is that it becomes really hard to do exposures when you don’t even realize you have a new obsession.

Enter the Internet. As I started exploring OCD forums on social media, I realized how common all my weird OCD crap was, even the stuff I thought was unique to me. For example, I always thought I was the only person who had the irrational fear of having done something horrible during a blackout after having two or three drinks. I knew logically that I couldn’t have blacked out, but without 100% certainty, I just couldn’t be sure. It was a huge relief for me to wind up on an OCD forum where a woman was inexplicably convinced that she had, in a completely sober state, blacked out and had sex with a man in the bathroom of a Panera, where she had gone to grab a sandwich by herself. Seeing people parrot my exact fears—or even more outlandish versions of them—was reassuring. If these people also had the same obsession, then maybe it didn’t hold much water. Maybe it was just OCD.

Unfortunately, the labeling of the fear as “just OCD” was another compulsion. I became addicted to these forums because they provided reassurance that my fears weren’t founded in reality. Lurking on health-related or anxiety-related forums to get reassurance continued to be a bad habit of mine. At one point I joined an OCD forum that tried to ban reassurance-seeking, which created a rift with one of the moderators who used the group to seek reassurance multiple times a day—she was scared that she was secretly a cannibal.

Another thing that happened on these groups was that people would confess to things that they were scared they might have done, or even just confess to having intrusive thoughts that they believed were significant. I saw obsessions I didn’t even know existed: people afraid that they were capable of hurting someone, people afraid that they didn’t really find their spouses attractive, people afraid of being secret racists, people afraid that they would never be sure of their sexual orientation.

I still have OCD, and always will. I’m not on medication (I’ve tried several; none really worked for me, and that’s common with OCD too. Most medications meant to treat OCD are really designed for depression.) But I’ve made improvements to the point that it no longer controls my life. When I get intrusive thoughts about horrible things that might happen, I try to respond to them with indifference instead of zeroing in on them. When my husband is late coming home, I don’t text him right away to see if he’s alive. I no longer post about my obsessions on forums to get reassurance, and I try not to even lurk anymore.

And most importantly, when I see a bunch of identical straws, I pick the first one I see instead of asking myself which straw will bring a curse upon my family.

I swear reading your substack sometimes feels like looking into a mirror. I also have “pure OCD” which went undetected during my teen years and early 20s. For many years, I was terrified I was secretly trans, because I couldn’t “prove” that I knew my gender identity. It was absolute hell and I shrank into myself, crying myself to sleep every night, trying different masculine voices to check if they “fit” - and this was all something that I couldn’t even begin to explain to friends (I had and have no problem with trans people at all!) I knew people wouldn’t understand.

Like you, I found forums and this led to extremely toxic, late night reassurance seeking. Eventually, my obsessions shifted and I began to see a CBT specialist which helped a lot. One thing that no one talks about with OCD is what to do when one of your obsessions comes true. I was worried about infertility for a year or two, and then - I couldn’t conceive and had to do fertility treatments. That was a real mind fuck. I have to remind myself every day that I didn’t cause it nor did I “predict” it.

Not sure where I’m going with this, except to say thank you for this post! I’ve really enjoyed subscribing and many of your posts really resonate.

Signed, an early 30s soon to be mom who also daydreamed about being a melancholy Victorian waif, struggles with making new friends, has zero passion for any of my jobs, and probably has ADHD to boot

I’ll be honest, I did not expect to get five dollars worth of reading out of this subscription but I really really do