I Wasn't A Horse Girl. I Was A "Victorian Orphan Girl."

Macabre and dramatic girls need representation too.

I feel like the “horse girl” archetype is pretty solidified in our cultural zeitgeist. We all knew or know a horse girl; perhaps we even know grown women who remain somewhat horsey, with their ballet flats, plaid scarves and gummy smiles. There has been some acknowledgement of dragon girls too, little girls obsessed with dragons, mood rings, and fantasy worlds, who usually have a necklace with some kind of orb-adjacent item embedded inside. But increasingly, I’m discovering other women who used to be a different kind of girl—the gloomy, dramatic girls who weren’t obsessed with horses or dragons, but instead derived their rich inner fantasies from germ-ridden Victorian tenements and workhouses.

I was (and probably still am) one of those girls. This is my story.

When I was six, my parents expanded our family and had my younger brother. As a family, we all moved from sunny, palm tree lined Los Angeles to a beautiful but shadowy Tudor style house in New York. The combination of a new sibling getting all the attention (I very much wanted a brother, but didn’t anticipate how much time I’d have to spend alone) and living in a foggy, cold and gloomy environment, on a haunted-looking hill, far away from kids my age, created a dramatic shift in my inner world too. I developed a fascination with a new type of character—a Victorian orphan.

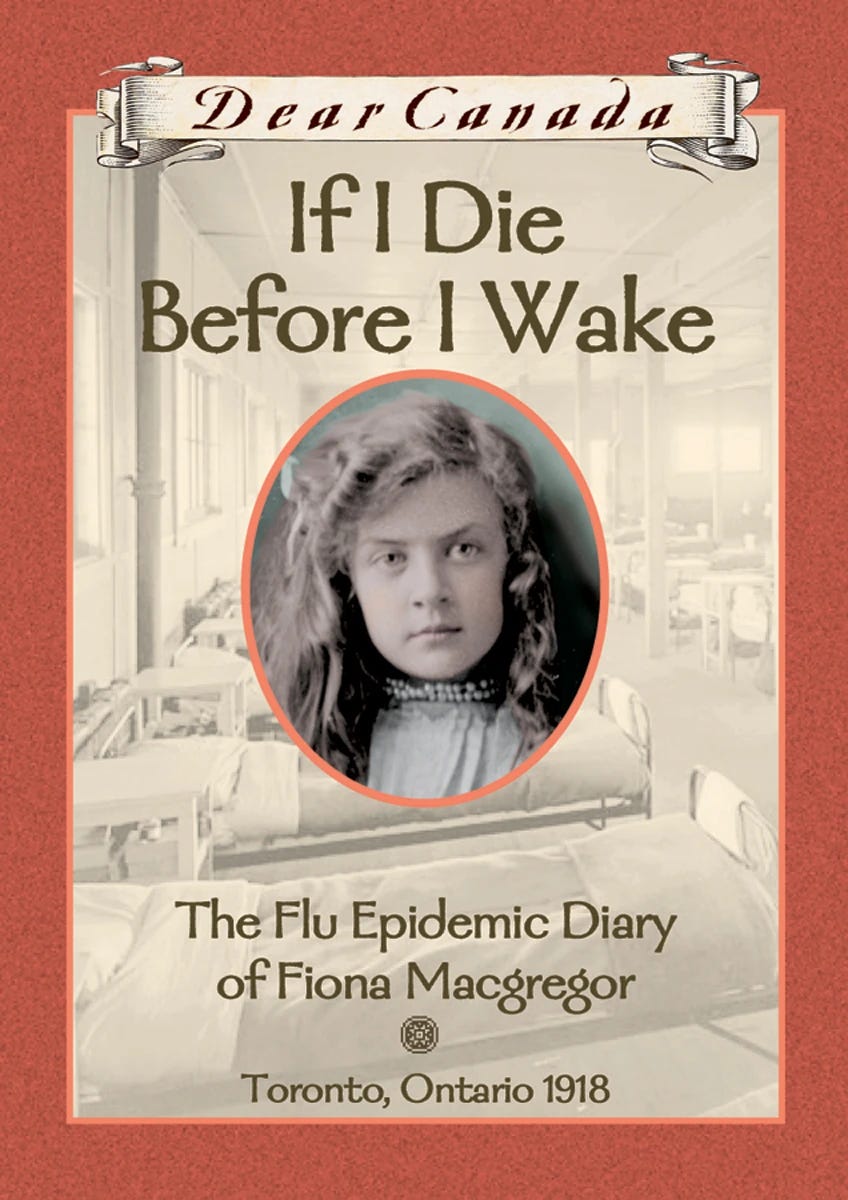

My obsession was not completely organic. Yes, my new house was the perfect setting for such a play-pretend game, but some forms of media were responsible. For one, my parents had recently taken me to see the musical, Oliver. (“Once you learned about Oliver Twist, your obsession with the plight of Cinderella took on a Victorian flavor,” my mom says. “When you were seven, when other girls dressed up as angels or princesses or cats, you requested I make you an Oliver Twist costume for Halloween. I was an enabler.”) I had also received Samantha the American Girl Doll as a “big sibling gift” when my brother was born (for those of you who aren’t familiar, Samantha was an Edwardian orphan who lived with her wealthy relatives in the exact same part of New York where I grew up.) My parents had also recently shown me A Little Princess (1995) and The Secret Garden (1993), both of which involved orphaned little girls in the early 1900s living in mysterious and gloomy locations, both with vivid imaginations (in A Little Princess, the main character has delusions about luxurious banquets while languishing in her evil Headmistress’s attic as an indentured servant.) As I immersed myself in the dramatic and romantic world of Victorian and Edwardian orphans, I found myself less and less interested in the idea of being a “fairy veterinarian.” Oh, the folly of my youth!

Granted, my life wasn’t actually tough at all. I had a privileged childhood, and even though my parents were busy with a new baby, they were on the more available end of the parent spectrum. To some extent, I wanted to be alone. I enjoyed the drama of it all; the staring out the window sullenly onto the frosty backyard, pretending for a moment that I couldn’t see the neighbor’s construction tarp or my own hot pink cheetah print bike.

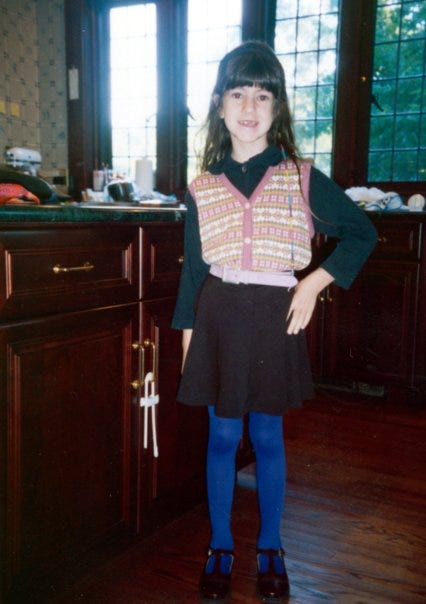

Winter, in particular, really drove this fantasy home. In Los Angeles, it never got very cold, but in New York, I got to experience a true winter. As a child who never really enjoyed getting dirty or sweaty—an indoor cat, if you will—I preferred to spend my winter weekends inside, drinking hot tea or cider and cuddling under a blanket. But what made this even more fun was slipping into thick cable knit stockings and patent leather mary-janes, curling my hair into ringlets by sleeping in overnight curlers, adding a grosgrain hair bow, donning a forest green plaid dress, and wandering around pretending I was at a strict boarding school. This, thankfully, put a pleasant spin on the times that my parents would tell me I couldn’t watch TV until I cleaned my room. I wasn’t really cleaning my room, I was merely the underage scullery maid being forced to work for table scraps!

To make matters more interesting, one staircase in my childhood home had a tiny storage space underneath it, which you could access via a tiny wooden door. This is not the real door, but it looked something like this:

All day long, I would find excuses to go into the tiny door, which I called the “hidey hole.” The hidey hole, typically, was where I would pretend to live. I would curl up in a blanket and shiver there while I imagined the cruel world outside me, where my parents were corpses in the Atlantic and whoever the hell was making spaghetti in the kitchen was merely the orphanage cook.

I experienced a bit of a culture shock when I started attending the local public school. Apparently, other kids my age had no interest in tuberculosis outbreaks within the cramped confines of a Victorian tenement. On my first day of school, I showed up a makeshift boarding school uniform—the aforementioned cable knit tights and mary-janes, but with a pleated skirt and lacy white blouse—and stood in horror as I realized nobody else was participating in my delusion. I had almost wanted my teacher to threaten to beat me with a ruler and make me wear a dunce cap, but instead she walked me to my desk with an insipid cardboard caterpillar spelling my “real” name instead of “Elizabeth Mary-Anne Hamilton.” The other kids were wearing bright primary colored sweatshirts and jeans, light-up Velcro sneakers and scrunchies. They were trading neon glittery stickers and turning staplers into machine guns. They were throwing Legos at each other and quoting Animaniacs. They didn’t understand what I enjoyed about pretending my parents were dead, or pretending I was slowly withering from consumption. Where was I?

Because I already had a hard time relating to others, and was so intensely focused on the world I had created in my mind, it was hard to make friends. I took interest in one kid, but my method to woo her involved leaving creepy notes on her desk chair instead of actually talking to her. I tried to invite a bunch of girls to a sleepover at my house when I turned eight, but half of them left before bedtime because my house “seemed haunted.”

Eventually, I did make a friend—a supplicating little girl named Chelsea who seemed to have no interests or opinions of her own. Chelsea became my perfect sycophant. With such an agreeable friend, I was always guaranteed an opportunity to play my games about dying on the Titanic or being locked in the attic of an orphanage. Frustratingly, though, Chelsea had zero background information on the historical backdrops of these games and would frequently get confused, believing us to be in modern day or asking when our parents would come to pick us up from the orphanage. To make matters worse, Chelsea’s parents spoke with my parents about me “giving her nightmares” thanks to some of my more morbid play-pretend scenarios. I also got in trouble at school for making a creative writing project about Chelsea and me on the Oregon trail. Apparently it was “mean” to accurately portray Chelsea slowly dying of typhoid fever in our covered wagon.

As my brother grew older and we developed a relationship (extremely close, but with some jealousy and tension, as is typical of siblings) my secret identity as a Victorian orphan was useful for any situation where I experienced sibling rivalry. One minute, I was a resentful older sister, annoyed that she was being asked to do her division homework while her younger brother got gold stars in preschool for knowing his colors. The next, I could be the ward of my family, sleeping in the hidey hole while the little lordling of the manor got his berries and cream (AKA: microwaved pizza squares.)

I asked my brother what he remembered about this time, and he said, “All I remember is you writing novels about starving children named Bridget and Felicity and then claiming you were adopted and I was the real child every time you got into a fight with Mom and Dad. You were obsessed with claiming to be a changeling, but in an obvious fake troll way. It was so fucking annoying. You’d say stuff like, ‘My brother is the smart one; he’s just like you. I’m stupid and I’m really from this other stupid family.’ Shit like that. So annoying. You were playing such 10D troll chess.”

My identity as a forlorn and abandoned orphan was a bit of a self-perpetuating cycle. I was drawn to this world because I was a bit lonely; I was socially awkward, sharing my parents with a new sibling, and living in a new town—even after we had been in New York for a few years, I felt different from the other kids who had all gone to preschool together. But on the other hand, the more I engaged with this type of pretend play, the more isolated I became. Other kids thought it was weird, and the ones who didn’t think it was weird, like Chelsea, were completely unwilling to study the source material. So I continued to spend many hours of my time alone. Once I learned to read and write clearly, I started spending a lot of solitary time in my bedroom writing books. “I remember you started, but did not finish, writing several book series about dynastic families,” my dad said. “You would write charts indicating how old the characters would be at different points in the story but then run out of steam. There was always an ominous moment when you’d bring a bunch of printer paper downstairs and staple it into a book.”

My mom remembers my books too. “The Gothic Victorian morbidity hit a height when you started writing stories of orphans living in threadbare conditions in 19th century England. You asked for books about the period so you could do research. One story completely threw me because the level of detail in its gloomy poverty both worried me about your mental state and delighted me because of your imagination and talent.”

My parents indulged me. They approved of anything creative, and I’m sure watching me walk around in a bonnet and apron was entertaining for them, as much as it may have been weird to hear me repeatedly claim they weren’t my real parents. It’s ironic, in hindsight, that my obsession with being unwanted and alone was part of an elaborate fantasy world, enabled by my extremely devoted parents who loved the parts of me that nobody else did. They took me to various historical villages over the summer, where I would stay in character the entire time. One time, I attempted to trick my little brother (then three) that the train to the historical village was a time machine, only to have my ruse foiled by an employee who referred to her butter-churning exhibit as “something people did back in the Colonial times.” (You may be wondering why I would participate in such an activity when my obsession was with Victorian England, not 1700s America, and to you I say: hello, fellow Victorian Orphan Girl- you’d have been a lot better at my games than that dolt Chelsea.)

The transition into summer’s warm breezes and sunny skies forced me to alter my inner world. I couldn’t very well pretend to be in a cramped and cold workhouse when I was on a beach vacation with my parents, eating at some beach side restaurant called Mr. Rusty’s Crab Dumpster. Often, the summer brought with it its own narratives: for example, my parents were actually my adoptive parents who rescued me from the orphanage, and this was my first time seeing the shore. I thought about A Little Princess less, and Anne of Green Gables more. Of course, all of this clashed with my experiences at day camp—being forced to wear garish, lime green T-shirts for a horrific game of tug and war, participating in various buggy and muddy obstacle courses, and getting yelled at by eighteen-year-old counselors for failing to perform the Macarena successfully. My sanctuary was the arts and crafts station, where I could pretend I was manufacturing goods as part of my work as a child laborer working under the grueling conditions of a London lanyard factory.

As depressing as my fantasy world was, there were bright moments. For one, my stories always had a happy ending. Yes, the parents were always dead and the main character usually endured misfortune throughout the story, but the finale (whether in a book I was writing or just in my pretend games) almost always resulted in the main character being adopted by a family who lived in a picturesque cottage in the English countryside. Sometimes, the “dead” parents would resurface, or the resourceful older sister would adopt her ten younger siblings after starting her own pie company. Often, I would have my own parents play both my evil guardians and my happy-ending adoptive parents. Either way, I didn’t revel in experiencing infinite distress—even my bleakest fantasies, I knew, would lead to a glorious ending, with a tea party in an overgrown wildflower garden.

Around ten or eleven, I lost interest in this world. My love of dolls slowly faded—I still posed them in little “setups” which I was adamant were parts of my room decor and not play-pretend. I had a Victorian doll house which I decorated with my mom, but I saw it as a hobby, not a toy. When I was thirteen, I collaborated with my a friend to “ironically” enter an American Girl Doll video contest where I played Samantha (and where Felicity is almost fatally injured after jumping off a balcony.)

Although I had always had crushes on boys, starting middle school put them more in the forefront and I couldn’t do anything, or enjoy anything, without thinking about how it would appear to boys. But I still had a flair for the dramatic and intense, and I found myself transitioning out of my melancholy Victorian narrative and into the identity of a mall Goth.

The experience of “going Goth” felt very much the same as my previous fantasy—it drew attention to me while allowing me to explain away the fact that I was alone, it aligned with me not having many friends and being mocked by most kids I met, and much like my Victorian boarding school uniform, aligning with a Goth persona enabled me to build an entire wardrobe around it—fishnet stockings, flame-print chokers, black fake leather skirts, black crop tops held together with safety pins.

What I didn’t know (and what I imagine most Goth 12-year-olds don’t know) was that this would only last for a year or two before I would look back on it as embarrassing (and later, kind of cute.) I would go through many iterations as I got older, eventually allowing other people inside and trying on personas that involved smiling and having friends (my J.Crew prep phase was fun, albeit not long-lasting.)

And here I am, approaching my thirty-fifth birthday, wondering if it’s time for yet another style and identity switch-up—I suddenly need more tweed blazers, rain boots, and chunky cotton sweaters. I want to be a preppy, classic British mother, in a Barbour jacket and well-worn Hunter boots, slick with dew and errant blades of grass. Or maybe I want to dust off those Jeffrey Campbell Lita boots I never thought I’d wear again, and become the 2012 Pumpkin Spice Girl that I shied away from at the time. I like to think that the Victorian orphan inside me isn’t gone forever—it was just emblematic of my flair for the dramatic and trying on new identities and styles. And I don’t think that’s ever going away.

I am laughing, because not only was I an orphan girl, not only did my parents take me to the Laura Ingals Wilder house in Mansfield MO for summer vacation (they had to bribe my brother with a side trip to an amusement park), not only did I run around in a sun bonnet my mom had sewn for me, not only did I imagine myself to be put-upon Sara Crewe whenever I had to do chores, but my favorite childhood game—which I invented—was actually called Orphanage.

And yes, I graduated to a goth and drama-club phase in high school. So glad to hear I’m not the only one!

Relevant SNL clip: https://youtu.be/eWBNCnU_PK0?si=3hmdhIxGIfOEsyVl