Why I'm Obsessed with Lonely Young People

My special interest has a long history

If you follow me on Twitter, you’ll likely notice that I post a lot about one particular thing: lonely, single, young people. Not only do I want them to be happier, I want them to find partners and get married and start families, if they want. You might also notice that I post quite a bit about my own life as a married woman in her thirties with kids, who met her husband a long time ago. You might wonder, “Why is she even preoccupying herself with this topic at all, let alone asking so many questions and voicing so many opinions? She’s barely dated herself, why does she care about the dating lives of strangers?” You might also wonder “Why does she think anyone wants to hear the endless not-very-good Trump impressions?”

Anyway, like many quirks of adulthood, it all goes back to my childhood. Specifically, a childhood of yearning to make connections with people- before I was concerned with dating or romance- and failing due to factors I couldn’t comprehend.

My family moved across the country when I was six, and I started at a new school. I was intimidated by the fact that the other kids were so much better at sports than I was (I am still painfully uncoordinated) and so fiercely competitive enough about it that they would yell at me for “making their team lose” during low-stakes T ball games in gym class. It was also daunting being the new kid, when all the other kids in school had memories together from kindergarten and preschool. I told myself that I wouldn’t be the new kid forever, and over time I would fit in with the others. But I didn’t. It felt like the more people got to know me, the less they liked me. I wasn’t invited to many birthday parties, and the kids who did invite me were quick to inform me that their moms had “forced them” to do so. I so desperately wanted a best friend. I made a few attempts, but it all felt forced, like I was pretending to have a best friend instead of actually having one. I would leave platonic love letters to other girls in hopes that they would be my friend; they predictably found this creepy. I didn’t understand why being friendly and outgoing wasn’t enough.

This was compounded by the fact that the other kids’ parents absolutely loved me. This is probably because I was a weird kid, and adults think weird kids are amusing. I was creative, I invented fanciful stories about my life, I had a grown-up vocabulary, I dressed myself in a makeshift British school uniform everyday despite attending public school in America (I was inspired by A Little Princess) and I was regularly chided in class for secretly writing comedy skits during math lessons. I made stop-motion animation movies with my Calico Critters. I created a newsletter that I would give my dad while he drank his coffee entitled “OJ: What Did He Do Now?!” I would hear fawning praise from every adult I met, about what a character I was, how “funky and quirky” I was, you name it. All the things that my parents told me were great about me were probably the things that other kids hated about me. I was, perpetually, “doing a bit.” As much as I wanted to connect with other people, I only knew how to do that by entertaining people. But parents can’t very well tell their kid to be more normal, or to dampen what makes them interesting. So the alternative, I assume, is you encourage your kid to continue being weird, as long as it doesn’t harm anyone, and let them suffer through social isolation that you hope is temporary. It’s also possible that my parents subtly told me to stop being weird and I didn’t pick up on it. Many such cases.

Once I got into middle school, I had gone from “bizarre kid who doesn’t get invited to birthday parties that often” to “the most unpopular girl in school.” I’m not exaggerating here. I was laughed at in the hallways by kids I barely knew, things were thrown at me, you name it. This probably boiled down to three factors: the aforementioned weirdness, the fact that middle school is typically pretty cruel, and the fact that unlike other weird kids, I wasn’t geeky! I couldn’t fit in with the AV Club or the kids who played D&D because I was a hyper-girly girl who loved fashion and scented shower gels and hair glitter.

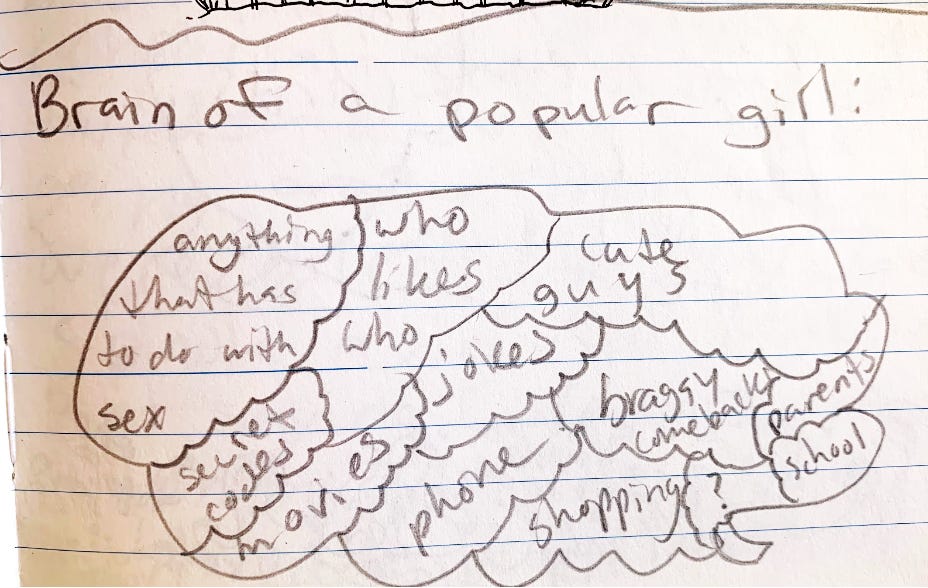

Although a big part of me just wanted close friends, even if they were geeky or awkward, I remember yearning to be part of the popular group. Those girls were the only ones who had boyfriends, and they seemed to exist in a perpetual floating hot-tub party. They looked effortlessly happy and nonchalant, whether they were rolling up their shorts and making oversized sweatshirts look cool in gym class, or sitting together in the back of the auditorium, rolling their eyes and saying “That’s so random” about the presentation being given by a refugee from Kosovo.

Once I realized that there was no way I’d ever be the popular girl I dreamed of being, I adopted a Goth persona that only opened me up to more ridicule, probably because it included me correcting all my peers who used my real name and informing them that I would hereby be referred to as “Volcanica.”

I was banished from numerous lunch tables (sometimes by vote, a la reality TV rose ceremonies), and asked out by boys as a joke (or, more often, asked out on behalf of boys, as a joke, by girls, who were doing it to embarrass the boys). The fact that I wore fishnet stockings and faux-leather skirts opened me up to rumors that I was promiscuous, which added insult to injury because boys weren’t even interested in me. I know at my age, it’s a bit pathetic to have feelings about the way you were treated by your peers in seventh grade, but I don’t hold it against any of them. They were kids! That doesn’t change the fact that the memories are there, and that all my formative years were spent wondering what was wrong with me, while nobody could tell me.

In fact, I asked! When a girl told me I wasn’t allowed to sit at her lunch table because “that would ruin what we usually do, which is making fun of you” I took her to the guidance counselor to ask what she didn’t like about me. She couldn’t articulate it. She stammered and eventually said “It’s just the way you are. It’s everything about you.” The guidance counselor sagely nodded and suggested she let me sit at her table for two days a week, and make fun of me on the days when I wasn’t sitting there.

I had one interaction in particular that seems kind of mild and innocuous when I talk about it as an adult, but it still haunts me. A quiet, slightly geeky girl in my class named Natalie was generally nice to me, and I wanted to become friends with her. So I did what I always did and attempted to “entertain” her. First, I announced to her that I was planning to enter the school talent show with a song I was writing, but I wasn’t finished writing it yet. I’m sure to be nice, Natalie said something like “Oh, cool,” and went back to doing what she was doing. I took this to mean she was deeply invested on the outcome of the song. A few days later we were entering the auditorium for some kind of assembly, and I spotted her. I cut past several kids to get to Natalie and notify her that I was almost done writing my song, and proceeded to sing a few lines of it. Things didn’t progress from there.

At this point, you might be thinking “Okay, she obviously had autism and nobody told her.” But apparently not! I was tested multiple times for basically every condition under the sun, because my parents, smart as they were, could tell that absolutely everyone my age found me annoying and off-putting. Granted, autism wasn’t detected in girls very well back then, but I’ve since been assessed as an adult—I have ADHD and OCD, but not autism. In fact, I don’t even test borderline. This could be because my obsessive fixations are about things that tend to throw these tests off—practitioners don’t believe that “autistic obsession with social dynamics and making social connections” is a real thing (and hey, maybe they’re right!)

Around my early teen years, I realized that there was a bit of a cheat code to the loneliness I was experiencing. I had more or less written off making a best female friend, or friends at all. But the boys in my class had entered puberty, and suddenly they were pretty forgiving of any personality defects in girls they considered “hot.” I realized that if I could just become hot, I wouldn’t have to worry about being alone, because I could find a boyfriend. That boyfriend would be a replacement for the best friend I was unable to find, and eventually he could even become my husband, and then I’d never be lonely again.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t that hot. I was skinny, but arguably too skinny (other girls regularly made fun of me for being flat-chested and flat-assed.) I also had pretty bad orthodonture, which meant that at least for a little while, I only had a few visible teeth on my top row. Then there was the issue of the unibrow and mustache—I looked a bit like a small Albanian man. So I took matters into my own hands. It would be easier to become hot—even if I wasn’t starting with much—than to get people under the age of forty to like me for my personality.

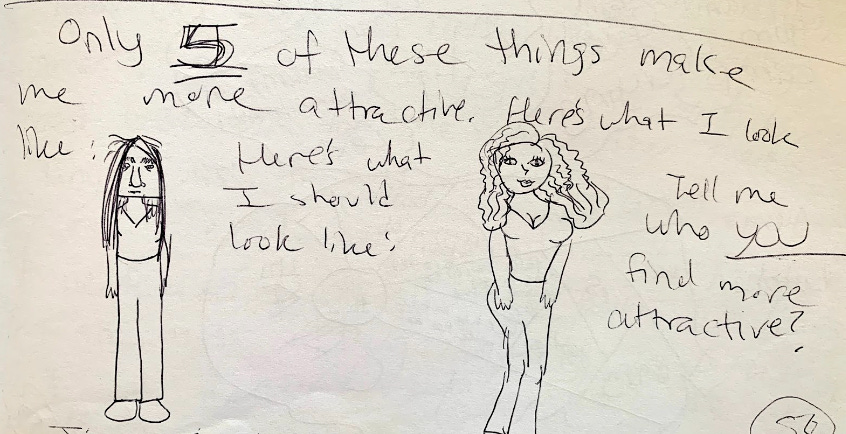

I became obsessed with my appearance. Relatives and family friends would try to kindly tell me to “focus more on my personality” but this felt trite and silly. My personality clearly wasn’t my strong suit. Maybe my looks weren’t either, but at least I understood what made someone hot. Hot girls looked like the girls in beer commercials and on saucy birthday cards for men that I saw at Spencer’s. I did not fully understand what a “good personality” looked like, especially because so many adults told me I already had one when I obviously didn’t.

I even created the original Virgin vs. Chad:

I would make long and detailed plans to become “hot.” Some of the main things I had my eyes set on were the following, some of which were physically impossible and some of which required convincing my mother, an ardent feminist who didn’t even wear tinted moisturizer let alone eyeliner, to approve:

Gaining weight, miraculously only in my boobs and butt

Lightening and curling my hair

Plucking my eyebrows and waxing my mustache

Not getting any taller, or even better, shrinking (I wasn’t that tall, but I correctly surmised that boys preferred girls shorter than them, and I’d have the most options if I never grew above 5’2”)

Acquiring more teeth

Wearing makeup

I was probably cuter than I gave myself credit for, because despite all my flaws, boys eventually did show interest in me.

High school was a bit better. I got less physically awkward—solidly cute—and I got in with an artsy theater crowd, and despite not really being into Theater with a capital T (or worse, Theatre) they embraced me because I was always putting on some kind of comedy show, not in spite of it. I had boyfriends and went on dates. But with all my experiences attempting friendship, I didn’t consider these friendships as any more significant than temporary insurance against lunchroom embarrassment. I acknowledged they could drop me at any moment, as so many friends had already done. And ironically, I wound up distancing myself from them when I got a boyfriend who didn’t think they were cool. As much as I yearned for friendship, I had very little faith in the friendships I did make.

You might be wondering why I didn’t consider boyfriends temporary. And I suppose I did, but I always held out hope that I would marry whoever I was dating. Unsurprisingly, I took breakups pretty hard, but I never spent too much time wallowing because I was looking for a husband and didn’t want to waste time. Does this sound psychotic, given that I was fifteen or so? Absolutely. But I’m not going to pretend that wasn’t my mindset.

After I actually did meet my husband in college, I still attempted to make female friends. I also still struggled to make connections. But over time, my social skills improved. I got some “feedback” from some people I knew—and I had asked for it, which I acknowledge is socially weird—about how I would be better off asking other people about their lives. The first thing I thought was, Why would I do that? Other people are boring. I’m much more interesting. I realized other people seemed boring to me because I knew nothing about them, because I never asked. It was incredibly hard for me to remember to ask the right questions, so I challenged myself to see conversations as a video game where I would earn points if I asked more questions than the other person did, and I would lose points if I talked about myself. For the most part, this strategy was actually successful.

I thought I had reached a good point by my late twenties, where I had put my past experiences behind me, learned from them (even if I was a bit late to the party) and was no longer someone who was immediately off-putting. And then I got a job that required a lengthy orientation offsite. At this offsite, I was introduced to several other women around my age who had the same role as I did. I couldn’t explain it, but I immediately knew these women were middle school popular girls. It wasn’t that they were exceptionally beautiful or charismatic, they just had a “vibe.” I wondered if they could tell that I was the girl who had to eat lunch in the bathroom. I told myself that was ridiculous—I was probably projecting. Grown women don’t bully. I decided that I would be super friendly, ask lots of questions, give lots of compliments, and not be weird.

Somehow, despite executing my plan perfectly (or so I thought), the women must have figured out that something was wrong with me. I noticed they were making lunch plans and excluding me. They even scheduled a bunch of activities around the city, including a Bachelorette viewing party and kayaking trip. I was invited to neither. I continued to be nice, figuring that maybe there was some miscommunication. But the exclusions kept happening.

At a group lunch, one woman announced she had to use the restroom and needed someone to accompany her (and they thought I was socially inept? lmao.) I offered to go with her, and she kind of paused for a second as if to ask “Anybody else?” On the way to the bathroom, I tried to strike up conversation about The Office, which I knew was her favorite TV show. She quickly said “Yep, good show” and hurried into a stall. She then fled the bathroom without washing her hands to avoid being alone with me.

I so badly wanted to ask them why. I even broke down crying in between training sessions, and a part of me hoped one of them would see, as pathetic as that sounds. I called my mom, who told me it was absurd to be this upset over “middle school girl drama” at almost thirty. And perhaps she was right, but this was more than just being excluded at a dumb work offsite. This was confirming that everything that had always been wrong with me—no matter how hard I scrubbed it away or worked to become better—was inextricably tied to me.

It’s because of all this that I spend so much time thinking about young single people who find themselves unable to participate in social life when the entirety of their age group only interacts on apps. That, of course, doesn’t mean that I’m an ally of hateful incels who want to enslave women in breeding farms, but those men are in the minority. There are so many young people—men, women, nonbinary, all orientations, you name it—who have never had a boyfriend or girlfriend, who have only been on a handful of dates, and who usually don’t have many friends either. I’m obviously lucky that I managed to navigate the romantic side of things pretty well, and I still feel like I scored way out of my league with my husband, who has always been effortlessly liked by his peers. But despite what makes me different from these young people, I feel so much like them in many ways. I know what it feels like to be on the periphery of a normal social life, and worse yet, to have no idea why you’re not part of it. I know what it feels like to try hard, and get told that you’re trying too hard, and then give up, and get told that you just need to put yourself out there. I can’t say I 100% relate, since my experience was a bit different, but I empathize.

And that, I suppose, is why I always post about them.

Realy relate to this post a lot, I've always felt alone and a bit locked out socially and this totally matches with my own experience. There's a type of existensal despair that comes from knowing that you're unlikable but being unable to understand why you're percived as such. Olivia Laing book The Lonely City is pretty great but one of the interesting parts is the way she examines how a lot of people just instictivley blame lonely people as being responsible for their own plight and seem to ignore just how self-reinforcing it is; Social connection beget social connections, while people find it extremely unpleasant talking to someone who's alone or gives off lonely vibes.

It's just so bizzare how paradoxicaaly the only way to escape is to somehow ignore it exists, or something.

This was a beautiful read - it also really encapsulates the nebulous state of being likeable and how impossible it can be to get people to see you the way you see yourself, or conversely - see yourself how others see you.