What Happened to the Hipsters?

to find out where they went, we must find out where they came from

One of my first articles, What Happened to the Neckbeards? followed the archetype of the fedora-tipping, leather trench coat wearing geek who was simultaneously obsessed with women, hated women, and terrified of women, all while assuming that he would get ass for opening doors. Perhaps I was too charitable, but my theory was that “neckbeard” wasn’t a permanent identity, and that many of these men grew up, stopped being neckbeards, and simply became regular geeks who married other geeks.

Lately, I’ve seen a few people asking the same question about hipsters, and having just written about 2010s nostalgia, I feel like I’m the person to answer the question. The modern definition of “hipster” depends greatly on whether the person using the term remembers the 2000s hipsters or the 2010s hipsters, but either way, they recall a quirky group of urban young people who seem to have disappeared.

I have a great deal of experience with hipsters, given that I have spent time in New York City and San Francisco, between the years 2005 and 2016. And I think to understand where hipsters went, you first have to understand who they replaced—and what made hipsters so different from all the other weird subcultures in recent history.

I recall the first hipster I ever saw. His name was Dustin, and he went to my high school in 2006. Tall, skinny, with the mismatching snub-nosed face of a cherubic 1920s baby and long shaggy hair, he was effortlessly cool and popular. He was part of the coolest rock band at our school, and on the school field trip, my dorky friends and I snuck out of the hotel room at night so we could look through the window and spy on the exclusive hotel party he was throwing (it was, regrettably, not that compelling.) He was the first straight boy in our school to wear skinny jeans—something that we assumed was reserved for gay guys (at the time, the assumption was that the bigger your pants were, the less gay you were, and straight guys were still terrified of looking gay.) In fact, Dustin was a bit androgynous, with his long hair, slender build and willingness to wear tight, brightly-colored clothing. In a way, this proto-Harry Styles was showcasing his masculinity in a way that was completely new to us: he was so virile and masculine that he could look a little bit gay, and it was okay.

Hipsters like Dustin were counter-cultural, but in a way that didn’t apply to the punks and Goths of the 2000s. Hipsters weren’t aligned with mainstream society, but they weren’t rebelling against it—they were simply too good for it. To be a hipster was to be “above it all.” Hipsters were into music you have never heard of, not because the music was weird and edgy but because you weren’t cultured enough to get the reference. Hipsters wore clothes you might have found odd, not because they wanted to shock you but because they were plugged into a world you could never dream of understanding. And to make fun of hipsters was to “punch up.”

This was probably why hipsters never publicly identified as such, the way Goths or punks might have. To identify as a hipster, or even admit knowledge of hipsters, was to eject yourself from the in-group. A Goth kid might have worn a flame-embellished T-shirt that literally spelled out the word “Goth,” but a hipster would never dream of wearing a quirky cardigan that spelled out “Hipster.” The first rule of hipsterdom was that you had to deny being one. Obviously, this changed over time—but in the 2000s, the “hipster who insists they aren’t a hipster” was a common meme. It was even mentioned in the 2013 movie, This is the End, where Jay Baruchel’s hipster-adjacent character denies being a hipster, while his friends quiz him on all the mainstream things on which he looks down.

I think that sometimes “hipster” gets conflated with “emo/scene kid,” as both subcultures flourished around the same time and wore skinny jeans, but they couldn’t be more different. Hipsters were upper-class coded, emo/scene wasn’t. Emo and scene culture borrowed greatly from anime, hipsters didn’t. Hipsters were specifically about being into obscure and artsy things—simply wearing skinny jeans did not make you a hipster.

In college, I had a brief encounter with a horde of hipsters. During freshman orientation week in 2007, I made the mistake of getting extremely drunk at a party. A few hipsters—including one guy in an ironic ascot and tweed blazer who went by the pseudonym name “Hymen Cavendish”—abscond with me and bring me to their dorm, along with a freshman boy in a popped collar polo shirt named Dave, who seemed equally oblivious.

I have limited recollection of that night, but I remember that Dave and I were brought in as a form of entertainment for the hipsters, who treated us the way Russian royalty in the 1700s might treat a dancing bear. We may have literally been asked to dance. We were also asked all sorts of questions, and they laughed at our answers, even if they weren’t funny. I realized I was probably being used for some kind of joke, but too drunk and out-of-the-loop to understand what it was, I continued to accept the free drinks they continually shoved in our faces. They let us sleep over on their couches, and the next morning, dressed us in insanely preppy clothing and took a bunch of photos of us meant to satirize the humorless, irony-free, painfully preppy school magazine. At the end of the ordeal, I recall feeling used and weird, but not fully understanding why. Nobody had touched me or said anything mean, but for a full twelve hours I was made painfully aware of how little I was in on the joke.

These same hipsters published a daily school pamphlet meant to be satirical (with Hymen Cavendish as editor in chief) but their jokes were always so esoteric and weird that the student body didn’t understand them and repeatedly groaned that it was pretentious. One day, the daily pamphlet was literally just a photocopied image of Jafar from Aladdin. When people failed to get the joke, the hipsters pretended to have abandoned the publication and handed it over to student government. Then, they proceeded to write terribly corny “normal” content for several weeks while pretending to be the staff of the school magazine, only to reveal that only idiots would have enjoyed the fake normal-person pamphlet.

Generally, people made fun of hipsters because their existence revolved around being better than everyone, and nobody but them being in on the joke. They were exhausting, annoying, and made everyone feel bad. They had a kneejerk negative reaction to everything people liked, and seemed to only like things that were objectively ugly, weird or unappealing to normal people.

But this iteration of hipster started to go mainstream in metropolitan areas around the late 2000s. This was when “hipster” stopped meaning “weird pseudo-preppy guy who wants everyone to call him Hymen” and started meaning “upper middle class tech worker who likes artisanal cocktails.” Part of this was simply that hipsters were getting older. There’s a limit to how far Hymen Cavendish’s antics could go in the workplace.

Hipsters had to tone down some of the weirdness and pretentious behavior to survive as adults. Perhaps some people still found them pretentious as they slapped mint leaves to release the essence as part of their painfully expensive mason jar Moscow mule recipe. But “you probably never heard of it” eventually transitioned into “I made it myself,” which is a lot more appealing to the mainstream. Thus, people who previously either didn’t like, didn’t understand, or didn’t know any hipsters were able to engage with this new sanitized “hipster culture.” Yes, perhaps it was all a bit twee and silly, but it was a bit more approachable. And who didn’t want to eat homemade stone-ground mustard?

By the mid-2010s, being a “hipster” was mainstream. It was no longer about being obscure and niche, or about knowing things nobody else knew. It’s striking that mainstream bands like Fun, Mumford & Sons, and their corny “stomp clap hey” music became synonymous with hipsters—Hymen Cavendish would never.

The hipster aesthetic going mainstream meant that the original hipsters—the ones who reveled in being into stuff nobody else was into—had to abandon their schtick. They either became mainstream “hipsters” themselves as they grew up and got real jobs, or they had to start doing something else to continue being sufficiently countercultural. I tried to look up Hymen Cavendish to see what he’s up to now, but I realized I actually don’t know his real name.

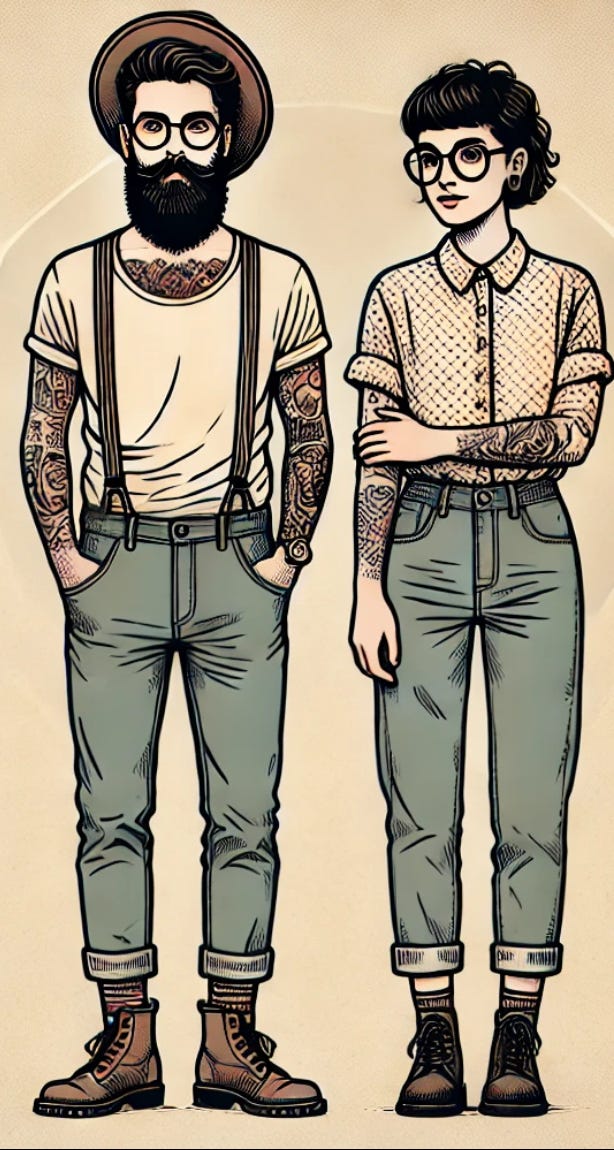

But now, things like craft breweries, home canning, modern farmhouse decor, food trucks, beards and tattoos are, if anything, painfully normal. They are the trademark of a city block that’s been “gentrified.” They are the Austin Instagram momfluencer’s favorite things. The male hipster aesthetic of suspenders, beards and undercuts now reads…almost a bit right-wing? Everyone is in on the joke now, which means the joke is over.

But young people still exist. Nobody is dressing like a 2000s hipster anymore, except perhaps ironically (actually, ironically dressing like a hipster is literally something a hipster would do.) But I think as long as cities and young people exist, there will be a certain cohort of pretentious kids who think anything normal is stupid, and anything weird is cool.

But today, I don’t think this group of young people can be as cohesive as hipsters of the 2000s were. As I’ve written about before, young people aren’t going out as much, and much of their socializing is done online. Micro-trends flourished in the TikTok fashion universe, where someone could identify as a coquette girlie, a big tiddy Goth gf, a gorpcore fashion girl, and a cottagecore tradwife, without having to go anywhere or do anything. Moreover, many of these aesthetics exist mostly in the online space, so people can have a “favorite aesthetic” that they never actually adopt themselves, in a way that anyone else can see. A big part of 2000s hipsters was being seen being weird, and showcasing just how exclusive and obscure you were.

If a hipster makes a reference nobody gets, but nobody is even there to hear the reference, is he even that cool?

I apologize for starting off with the most hipsteresque thing I've ever said, but you might be too young to grasp the first wave of hipsters - they were thick on the ground by 2002-2003. (A couple of good delineating points - the record store employees in High Fidelity aren't hipsters, but a lot of dudes who saw that movie and "got into vinyl" are; American Apparel and their Polaroid porn aesthetic shows up around this time; craft cocktails bars become a thing; most of the indie rock bands you'd most associate with hipsters had breakout albums by 2004.) Any 16-year-olds you're encountering in this style are just reflections of older siblings and media, and Hymen and company are more of an aggro "weird out the normies" subculture that's ever-present in high school/college; a clothing update for the kids in The Craft. Their modern equivalents are off shitposting somewhere as we speak, and probably in the tank for Trump.

As too what that hipster wave was, I think a lot of it was rejecting modernity (which at the time was the War on Terror, an ascending Republican majority and a suddenly pop, teen-infused popular culture) in favor of a cheap (the dotcom hangover was in full swing), thrift store aesthetic where you could deep dive into things and then annoy the fuck out people with holier-than-thou pissing contests about it. It overlaps with peak Lit Bro and a couple of other trends the internet still complains about despite having long vanished. Oddly enough craft brewing wasn't a big part of it - that group seemed to be an older, less cool crowd.

You're right that around 2010 it shifts to a new, porkpie hat and suspenders, craft brewing, distressed wood style. The Great Recession pushes a lot of people into the small-craft lifestyle around this time - I met my first twenty-something stained-glass artisan married to a professional woman hereabouts - and gentrification becomes the huge argument of the day. There's probably an argument to be made that Obama's success, plus Republicans the administration as hipster (remember the dustup about the guy in the Obamacare ad in glasses and a pajama onesie?) pushing a lot of people into being hipster-lite. Then it all collapses in the mid-2010's and people move on to other styles, with the stereotypical hipster remaining only as a strawman for internet debates.

As to where are those types of people now? Mostly off the internet, I suppose. Everyone likes to say streaming algorithms killed hipsters, but they're still behind the scenes pushing most of the content on streaming: https://www.vulture.com/2023/04/spotify-discover-weekly-songs-essay.html I think the context collapse of social media pushes a lot of this stuff out of view - when you truly want to avoid it, you don't move out to the country and make farm videos, you just... don't post things publicly. You just go about your day with niche fashions and niche interests, and the world at large doesn't know you exist.

Another important element of the downfall of hipsters is the ubiquity of streaming. Even during the time of the early internet, if you wanted to find, say Moondog or Captain Beefheart, you had to already know who they were, whether it be by listening to college radio or reading about them, and then be willing to make the trek to the local record store and talk to a clerk who Knows About Such Things as part of an initiation rite. Now, you can just go to Spotify's curated "American Originals" playlist and listen to Connie Converse or the Shaggs and call it a day.

To be clear, I think that the leveling of culture is in many ways really great! There's tons of music that is getting inifinitely more exposure than it would have otherwise. But with exposure comes a loss of cachet, and cachet was the bread and butter of hipsters.