Too Pretty to Work (Part 1)

Why more young women are turning away from The Girlboss

BTW, you can read Part 2 here.

Before I get into this, I want to make a couple things clear, just to get ahead of the nonsense:

I’m going to get into why, especially these days, so many young women are souring on having or valuing a career. The issue is multifaceted, and some of the reasons are ones I even relate to, so this doesn’t come from a place of me being a judgmental career woman, looking down on the idiots who don’t see the value in working.

I know that many young women still do want to work, I can’t possibly include every single person’s life story in one article, however I’m referencing a general vibe I’ve noticed, especially on social media, of it becoming “cringe,” almost, to value your career.

The title is meant to capture the overall sentiment I’ve seen on social media which I’m aware is often tongue-in-cheek; I’m not implying that any young woman who feels negatively about work genuinely believes she’s too pretty to work.

I’m going to get into the first three explanations for this phenomenon in Part 1. Part 2 will cover the rest. So if you want to read more, please subscribe!

Anyway…

In 2016, I Pokemon went to the polls, as they say, wearing a bubblegum pink pants suit. I was confident Hillary Clinton would win the election, and it was a great moment in time for slightly corny liberal white women with office jobs like me. I wasn’t in love with my job, nor was I necessarily that good at it (I was reprimanded for “going on Reddit” during work hours) but it was a big part of my identity. My dream was to become a people manager before thirty. Although I didn’t use the word “girlboss” to describe myself (I wasn’t that obsessed with my job- I prioritized spending time with my husband and playing Sims) the term “girlboss” wasn’t yet a sarcastic insult hurled by pickup artist influencers trying to hawk their Patreon to mewing teenagers who recently graduated from their Skibidi Toilet era.

It was an era for the Wizness, the woman-owned business, as Ilana Wexler on Broad City (where Hillary Clinton famously made a guest appearance) would say. Although Ilana wasn’t a successful woman (she worked at a second-rate Groupon and got in trouble for wearing a dog hoodie to work—my kindred spirit, honestly) she had the vibe of a girlboss, or at least an aspiring one. Also popular at this time was Sophia Amoruso, real-life CEO of the clothing company NastyGal (anyone remember those edgy 2010s clubbing dresses?) who literally wrote the book #Girlboss.

I also noticed that more and more women in my social circle were becoming nebulous “girlbosses” without a clear company they founded or industry. I met a woman at a networking event and I followed her on Instagram to see that she posted extremely long content about her various webinars, self-published books and inspirational speaking about “disruption.” She didn’t actually seem to have founded a company. The company was the talking about it. Nothing is safe from grifts.

In the months and years after 2016, the term girlboss—and with it, the archetype of the career-minded yet feminine young woman wearing heels with a neoprene royal blue blazer—was gone. I didn’t notice it at first, especially because it wasn’t a huge part of my own identity—I often felt a bit out of place with the real serious “women in tech” types, despite being a woman in tech myself. But by the time 2020 rolled around, the change in how young women talked about work was striking to me. And in many cases, I understood exactly where they were coming from.

1.) The Cycle of Cringe

I give Hillary Clinton too hard of a time for how she became “cringe” so quickly and so easily (truly- it shouldn’t be her job to be cool!) But during and after the 2016 election, I saw a new “type of guy” emerge (or more realistically, type of girl.) These were the pussy-hat-wearing “resist libs” who would have Twitter profile pictures with black cat-eye glasses, cheekily holding up a mug with “Lock Him Up” printed on it. These people were not all women, but the women—especially the middle class to upper middle class white women between thirty and fifty—seemed to bear the brunt of the “cringe” accusation. For a long time, I’ve believed that seemingly random derision of this particular group has a lot to do with people’s mommy issues.

There were some perhaps-legitimate criticisms of this type of person—that she was mainly concerned with the “blue team” winning and less concerned with the plight of actual oppressed people—from a workplace perspective, concerned with things like “unfair dress codes” and the “glass ceiling” while refusing to pay people below her a living wage. But a lot of what I saw online was basically: this is cringe now, you guys lost in 2016 and we don’t want to be associated with you.

Along with the archetype of the sassy resist lib woman (who for some reason became synonymous with wine moms? Not beating the mommy issues allegations, I’m afraid!) the “girlboss” faded into cringedom. It wasn’t that people thought it was bad for women to work, or bad for women to be successful, but there was something suddenly embarrassing about considering yourself a “career lady” after career ladies ostensibly took a big Coolness blow. You might be thinking, “That’s dumb, why should women be punished for Hillary Clinton losing after Trump waged a misogynistic campaign against her?” and hey, no disagreement. I’m just calling it like I see it! You might also be thinking, “Well, speak for yourself, I didn’t have this reaction!” and to you I say: great! I’m not talking about you!

Unfortunately, the online landscape is based on a foundation of things being cringe and therefore unacceptable. 2016 marked not only the defeat of the penultimate “girlboss” and her aforementioned colorful pants suits, but also the introduction of an era where people were more online than ever, everyone eager to deride things that they decreed no longer cool.

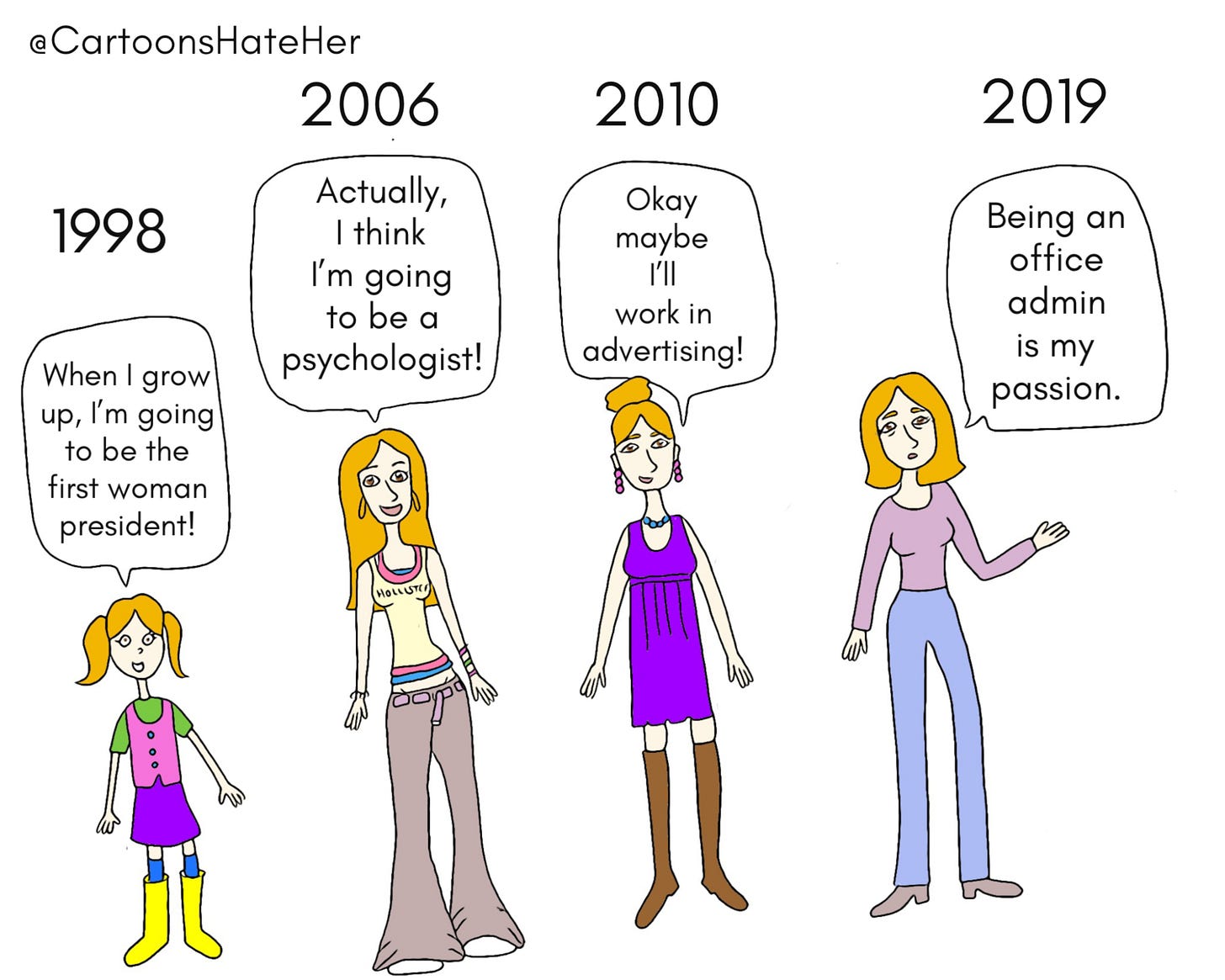

2.) Broken Dreams

When I was growing up, I aspired to be a full-time writer (and here I am at almost 35, still several thousand paid subscribers short of this dream.) I wanted to get married and have children, and I knew those aspects of my life would take priority, but I also planned on becoming a bestselling novelist. I didn’t even think about what my husband would do for a living, because in my mind, I was going to be the main breadwinner when I published my books about Victorian orphans named Bridget pensively looking out onto the moorlands. (I wound up writing a book of short memoirs about being a socially inept young married woman in the San Francisco tech world- the feeling of isolation is probably similar to Bridget’s, anyway.)

It was easy to be “career minded” when my imagined career was my passion. But as my actual career—a tech career, and not the $300K/year software developer jobs you’re thinking of—deviated from that dream, I found myself becoming less and less of a girlboss, especially when I noticed the glaring contrast between my colleagues whose dream was their job, and me.